Tamburlaine’s perverse will makes words come true. Metaphor and hyperbole are realized. When Tamburlaine literarily uses Bazareth as his footstool and has the Kings of Trebizon and Soria draw chariot, his boastful words are fulfilled but the effect is absurd. Words and reality seldom meet like this. What is a fact words cannot be altered by words. As Theridamas reminds Tamburlaine after Zenocrate’s death:

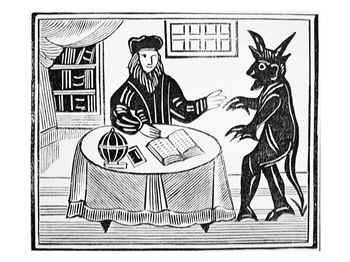

In ‘Doctor Faustus’, Marlowe continues this exploration of the nature of language and demonstrates the dangerous dichotomy between words and reality. Anything can be said but, if not grounded in actuality, it may be meaningless. Faustus’ flight of fancy about how he will use power reveals the potential of words :

He intends ‘to gain a deity’:

Instead of merely inventing such daydreams, content with the words (which would have made him a poet), like Tamburlaine, he tries to make them come true. The truth of what actually happens measures the distance, in this instance, between words and reality. His achievement is mostly trivial and at best deceptive, because the means violate the end. He thinks he will be ‘a mighty god’, but the power he acquires depends on subjection and in the attempt to free himself he relinquishes freedom. He is unconsciously penetrating when he says:

This, an expression of Renaissance arrogance, affirms a vast potential:

Faustus, however, fails to recognize the limitation implicit in the word ’man’: ‘this quintessence of dust’, though earlier, he has acknowledged:

It is precisely in the mind that man can be dominant. His power is in the realm of words. But Faustus rejects the value of his former learning and, by selfishly attempting to extend his influence over the external world, vies with God. Faustus is seduced by words. Apart from his ‘own fantasy’, he admits to Valdes and Cornelius :

Valdes’ sonorous and exotic hyperbole are indeed persuasive:

Rhetoric is by nature partial and one sided. The price of such a Pyrrhic victory is not mentioned. Though some of it is true, it is not the whole truth. The use of simile diverts attention from the fact that ‘spirits’ are being described. Their multifarious disguises suggests something sham and hidden. On analysis, this specious rhetoric is empty. The spirits may be beautiful but they are ‘airy’. They are only ‘like’ real women, simulacra. Their ‘beauty ‘, if this is debased term be allowed, is merely illusory. The vocabulary of voluptuousness is impressive and plausible. Words seem less adequate to describe the state of sin or the attractions of heaven, until they are known and believed in. After successfully invoking and dismissing Mephostophilis, Faustus with blasphemous irony, boasts:

His words seem to have power, but he is pathetically deluded. He shelters behind reassuring language. When Mephostophilis at first appears, Faustus says:

‘Ugly’ is singularly weak, applied to a devil. Faustus’ statement, rather than passing a judgment on Mephostophilis’ evil nature, expresses mere displeasure at his outward appearance. In asking Mephostophilis’ to disguise himself, it is evident that Faustus cannot stomach unsavory truth. Mephostophilis’ change is only external. Essentially nothing has changed. Evil is hideous but can be glossed over. Faustus is kidding himself. He understands that words can be empty (though perversely doesn’t accept that his own are):

Words per se are impotent and meaningless if they are not meant or accepted. Faustus says ‘I think hell’s a fable.’ For him there is nothing behind the word, it refers to nothing. Mephostophilis, who knows the actuality of hell because he is in it, replies:

Later, Faustus does experience hell. The word ‘damnation’ is empirically tested and Faustus finds it valid. Having signed the pact and sold his soul, Faustus blasphemously reiterates a phrase which Christ used in different context: ‘consummatum est.’ The irony is that Christ died to save men’s souls. The phrase is true in more than the local sense (‘this bill is ended’), however. Faustus himself is finished. Faustus is characteristically hyperbolic. His words are bravado. When he is wavering and nearly repents (II i), he steels his determination with a sadistic fantasy:

Though he doesn’t do so, the vicarious violence of the language pushes him over the edge. He is drunk with the possibilities inherent in words. However, one can become inured to words. The medium modifies and mitigates reality. Words, like horrific T.V. images, cease to have significance after a certain point when overloading of one’s sensibility occurs. Later, (II ii), when he has done the deed, he again has scruples, but he confirms himself in sin with another hyperbolic boast:

He uses words as Dutch courage. Truth is elusive and logic through the medium of language necessarily imperfect means to discover it, since sufficient information can never be taken into account. Faustus’ enthymeme:

leads him to a conclusion that would be right for him:

Yet, one of his premises is false: he is not man but spirit (according to the pact.):

In an orthodox theological sense, this is accurate but nevertheless the Good Angel has offered hope:

Therefore apparent truth lies and false reasoning for once gives Faustus the right answer. The ambiguity of language is made explicit and dramatic (II i):

Such duality of meaning derives from alternative versions of reality, Words can be variously defined. As a man is, so he defines. The way Faustus construes and uses words indicates his outlook. Faustus is persistently frivolous when he talks about evil. He is not aware of its significance nor of the implications of his change of state. Before being shown the pageant of the seven Deadly Sins (II ii), he ironically remarks:

Lucifer, however, reprimands him:

Faustus’ very diction is dictated by his state of sin. There is a constant use of irony implying the observations already made about language. It is most dramatically powerful and sustained in Faustus’ apostrophe to Helen.

begs Faustus, but with that transitory osculation he exchanges eternal bliss in heaven for the endless torment of hell. Faustus is employing conceit of conventional love language when he says:

but, in this case, it is actually true. His soul is in reality lost. Helen (whose name appositely contains the word Hell) is an illusion supplied by Mephostophilis, perhaps even a succubae. At a moment of ostensible fulfillment, Faustus is embracing hell.

However, hell is not in her lips and Helen is the dross for which he sacrifices all. Words are devalued and perverted as Faustus’ mind is corrupted. The gap between appearance and reality, his words and their meaning, is that between Faustus and Heaven. Divorced from the context, this speech seduces the audience into an admiration of (rather than a sympathy with) Faustus, which is inconsistent with a tenable attitude to the play’s morality. Though Faustus is deluded and pathetic, he does not seem so. His rhetoric is splendid and forceful, but it is merely rhetoric. Faustus is adequately warned, yet he chooses to ignore warning, Any combination of words does not necessarily constitute truth, and Faustus believes that his advisers are mistaken. The Old Man speaks eloquently and persuasively and Faustus is almost convinced:

However, to Faustus, Mephostophilis’ words prove stronger reason for not repenting. Whereas the Old Man moves Faustus to say: ‘I do repent, and yet I do despair,’ Mephostophilis forces him to recant: ‘I do repent I e’er offended him.’ The protean quality of a word enables it to express in different contexts diametrically opposed ideas. This debasement of the word’s significance represents a corresponding vitiation of Faustus’ values. Faustus dies in a superb coup de théâtre. Significantly, even amongst his last words, there is irony. His

quoted from Ovid’s Amores’ (I xiii 40) is, in its original context, the lover’s exhortation in his mistress’ arms. Faustus is in deadlier earnest and the new context enhances its effect (unlike his depreciatory use of ‘consummatum est.’) However, he has to leave pleasure and pay its price. His final words are painful but unavailing. As he is snatched down to hell, he can only utter ‘fearful shrieks and cries’, but that is a reaction more primal, immediate and sincere than any words and perhaps closer to true communication.

|