Human consciousness is time-based. Any piece of language refers to time. Words move in time from a beginning to an end. Verbs have a tense.

Poets, faced with the ineluctable fact of their own mortality, have understandably, always been concerned with time. So much so that the word was given a capital letter and, confused with its effects, came to be looked upon as an agency rather than an artificial way of considering the process of the Universe. The idea of 'Tempus edax rerum' is immemorial and is present in classical writers like Vergil (Georgics iii 284) and Ovid (Metamorphoses xv 234). Horace's rueful cry: 'Eheu fugaces … Labuntur anni' is Everyman's. The concept of Time's irresistible, destructive and irrevocable onrush an inevitable commonplace.

The Romantic locus classicus on Time is Lamartine's 'Le Lac' quoted from in the epigraph above. Most of the English Romantic poets shared similar feelings and thoughts on the topic. For instance, Wordsworth laments that he is 'unprofitably travelling towards the grave (The Prelude Bk I 267). Byron condensed the whole ethos in the famous last stanza of Canto XV of Don Juan (unjustly attacked by Eliot in his essay on Byron):

The eternal surge

Of time and tide rolls on, and bears afar

Our bubbles; as the old burst, new emerge,

Lash'd from the foam of ages; while the graves

Of empires heave but like some posing waves.

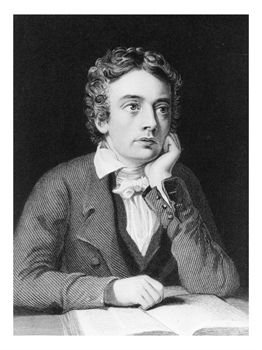

Keats, likewise, is concerned with the effects of Time. Endymion, Lamia, Isabella, The Eve of St. Agnes, and the two versions of Hyperion, the bulk of Keats' poetical output in fact, all have an element in common: their setting is the past. At first, this may seem a kind of Nostalgia. Apparently, things are not what they used to be. For instance, the beginning of Lamia refers to a time:

before the faery broodsDrove Nymph and Satyr from the prosperous woods,

Before King Oberon's bright diadem,

Sceptre, and mantle clasp'd with dewy gem,

Frighted away the Dryads and the Fauns …

(ll 1-5)

The old order changeth, yielding place to new. Satum and Hyperion are deposed in an unavoidable process of change.

Change is intimately correlated with time and only by perceiving changes are we aware of the passage of time. But change may be construed in many ways. It could be seen as progress, or change for the worse, or merely as the turning of a wheel like the cycle of the seasons.

The seasons revolve throughout Keats' poetry. 'In a drear-nighted December' and 'Ode to Autumn' are the mostobvious examples. The 'music' of Autumn is as important as 'the songs of Spring' ('Ode to Autumn', Stanza III). Keats compares man's life to the four seasons (vide Sonnet: ' Four seasons fill the measure of the year'). Growing old and dying is natural and inevitable. The endless cyclical recurrence of the seasons is analogous to that of the 'hungry generations' ('Ode to aNightingale, stanza VII).

Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose. The human condition remains constant. Keats recognizes this when he hears the song of the nightingale:

The voice I hear this passing night was heard

In ancient days by emperor and clown:

Perhaps the self-same song that found a path

Through the sad heart of Ruth, when, sick for home,

She stood in tears amid the alien corn;

('Ode to Nightingale,Stanza VII)

The night may pass, but the nightingale will continue to sing the same song, and human listeners to feel the same human emotions. The author of Ecclesiastes says it all:

The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be;

and that which is done is that which shall be done:

and there is no new thing under the sun.

Things are what they are used to be.

Keats' attitude to the past is neither sentimental nor naïve. The ideal romantic world of The Eve of St Agnes is put in a harshly naturalistic context. The last stanza qualifies everything that has preceded. The past is seen as past. Love itself is subject to Time. Time leads to death:

they are gone: aye, ages long ago

These lovers fled away into the storm.

…. Angela the old

Died palsy-twitch'd, with meagre face deform;

The beadsman, after thousand aves told,

For aye unsought for slept among his ashes cold.

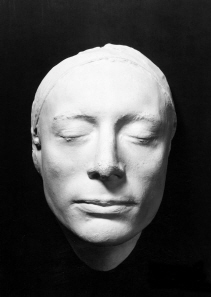

His medical training, and nursing of his dying brother Tom meant that Keats was fully aware of the concrete reality of death.

In Stanza III of 'Ode to a Nightingale', Keats gives a pessimistic and strikingly concrete description of the human condition:

The weariness, the fever, and the fret

Here, where men sit and hear each other groan;

Where palsy shakes a few, sad, last gray hairs,

Where youth grows pale, and spectre-thin, and dies;

Where but to think is to be full of sorrow

And leaden-eyed despairs,

Where beauty cannot keep her lustrous eyes,

Or new love pine at them beyond to-morrow.

Both 'Beauty' and 'Love' are at the mercy of Time, w

hich like La Belle Dame is 'sans merci'. The knowledge that Beauty must die, and that Joy is evanescent ('Ode on Melancholy' stanza III) results in a feeling of melancholy, characteristic of Elizabethan fin-de-siècle pessimism. Life is a melancholy goodbye, a leaving. Keats has a keen sense of Time continually passing:

Time's sea hath been five years at its slow ebb.

Long hours have to and fro let creep the sand

(Sonnet : To A Lady seen for a Few Moments at Vauxhall)

On occasions, Time seems to accelerate:

Minutes are flying swiftly

(Sonnet : On Receiving a Laurel Crown from Leigh Hunt)

(This line has a significance beyond its immediate context).

Keats echoes the urgent words of damned Faustus about to die (vide his final soliloquy in Marlowe's Dr. Faustus):

O that a week could be an age …

So we could live long life in little space,

So time itself would be annihilate

(Sonnet to John Hamilton Reynolds)

He is acutely, sadly aware that everything is transient. The poem 'In drear-nighted December', while affirming the continuance of life and recommending stoical acceptance, expresses anguish for impermanence:

were there ever any

Writh'd not at passed Joy?

(stanza III)

Keats speaks of 'the transient pleasures' ('On Death', appropriately among the 'Posthumous and Fugitive Poems') and 'fleeting blisses' ('To - ', ' Think not of it, sweet one, so'). The existential paradox : 'O 'twas born to die' could lead to despair or stoical resignation. Either way, a little mourning is in order:

all things mourn awhile

At fleeting blisses,

Let us too!

But this is also an urgent reason (by a variation on the carpe diem, carpe florem theme) for making the best of it while

one can:

diem, carpe florem theme) for making the best of it while

one can:

but be our dirge

A dirge of kisses.

Yet the unsatisfactoriness of life may also produce a death-wish. Death could be eagerly looked forward to as the end of pain and of a life subject to 'the rude/ wasting of old Time' ('On seeing the Elgin marbles'). The short poem 'On Death' reveals Keats' world-weariness :

Can death be sleep, when life is but a dream,

And scenes of bliss pass as a phantom by?

The transient pleasures as a vision seem,

And yet we think the greatest pain's to die.

How strange it is that man on earth should roam,

And lead a life of woe, but not forsake

His rugged path; nor dare to view alone

His future doom which is but to awake.

Of course, the poem is conventional, even trite. The consolation which it offers – of some kind of heavenly state after death where one will be more alive – seems too facile and unconvincing *, but its regret for the human condition is genuinely felt.

-----------

* Elsewhere,death is seen as final. For instance Keats writes in a letter: 'Land and sea, weakness and decline, are great separators, but death is the great divorcer for ever.'

-----------

Again and again, Keats expresses a similar longing for all-curing death: I have been half in love with easeful Death, Call'd him soft names in many a mused rhyme To take into air my quiet breath...('Ode to a Nightingale, stanza VI)

Yet would I on this very midnight cease And the world's gaudy ensigns see in shreds; Verse, Fame and Beauty are intense indeed, But Death intenser – Death is Life's high meed.

('Darkness' Sonnet: 'Why did I laugh tonight?')

However, in a different mood, death is undesired:

mortality

Weighs heavily on me like unwilling sleep,

And each imagin'd pinnacle and steep

Of godlike hardship, tells me I must die

Like a sick eagle looking at the sky.

(Sonnet : On Seeing the Elgin Marbles).

Time leads to death and death ends time, yet both time and death can, in a sense, be conquered by Art. Artistic beauty is not subject to natural laws:

A thing of beauty is a joy forever:

Its loveliness increases; it will never

Pass into nothingness;

(Endymion, ll 1-3)

Ode on a Grecian Urn explores this idea in detail. The work of art is outside time. The creator of the Grecian Urn and those depicted on it are all long dead but the object itself survives autonomous:

When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours...

(Stanza V)

The work of art ('All breathing human passion far above') transcends the human condition, characterized by 'burning forehead' and 'parching tongue', symptoms of time. But this is cold consolation for suffering humanity. The Grecian Urn is impersonal, a 'cold pastoral'. Though the love represented on it never dies it must remain unconsummated, in contrast to real human love which can be consummated but inevitably passes. The consolation of art is strictly limited.

However, works of art can give us a notion of the timeless :

Thou silent form, dost tease us out of thought

As doth eternity

(Stanza V)

A timeless stasis is produced in the beholder. Keats describes such an eternal moment in the sonnet 'On First Looking into Chapman's Homer'. The works of Homer have survived time, and reading them gives Keats a transcendental experience:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He stared at the Pacific – and all his men

Look'd at each other with a wild surmise -

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

The last line marvelously conveys a feeling of timelessness and stillness.

But, according to the 'Darkness' sonnet, death is 'intenser' than 'Verse' or 'Fame'. In the sonnet 'When I have fears that I may cease to be', the poet confronts the possibility that he may be nipped in the bud like Lycidas, and die before he has had time to produce works which would ensure his literary immortality and posthumous veneration. In a letter to Fanny Brown, Keats writes : 'If I should die … I have left no immortal work behind me'. He would be like Chatterton 'a half-blown flow'ret' (Sonnet to Chatterton). In such a case, death is a cause of 'fear'. Keats is man at the extreme, an individual facing the fact of his own death; a death which for the existentialist is final and makes life (even love and fame, the immortality which, in Ovid's phrase, art offers) meaningless:

then on the shore

Of the wide world I stand alone, and think

Till love and fame to nothingness do sink.