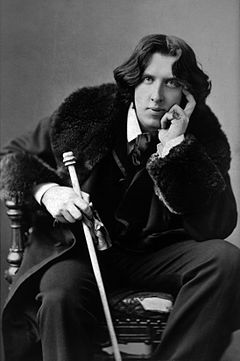

‘Much speech leads inevitably to silence’ Lao Tzu : Tao Te Ching Book 1, V I Pointed anecdote: once Wilde was being interviewed on his way to the railway station. He displayed his usual brilliant wit. But, unfortunately, it was announced that the departure of the train would be delayed. Having exhausted his ostensibly off-the-cuff (though in fact, carefully prepared) bon mots, he dried up completely and could say no more. Wilde, the playwright, delivered his lines like an actor in one of his plays, but it was a dramatic monologue not true communication. Words served to ward off embarrassing silence. To one who could say ‘I am prepared to prove anything’ (The Decay of Lying) and ‘Truth is entirely and absolutely a matter of style’ (Ibid), words could have been at best an amusing game. An attitude that surely betrays despair of language. II Lord Henry speaks a bit like Wilde. His is certainly the dominant rhetoric. He speaks the first words in the book (8) and his name is the last word uttered (242). Not content with the words that others use, he even wants to invent his own language, to name things anew like God or Adam (214):

Lord Henry dominates the speech of others, and they repeatedly refer to his words:

Though he uses the phrase ‘Upon my word’ (8, 63), Lord Henry is a liar. As Lady Agatha says : ‘He never means anything that he says’ (47), and Basil corroborates this : ‘You don’t mean a single word of all that’ (86). Lord Henry admits that he lies to his wife: we tell each other the most absurd stories with the most serious faces’ (10). However, (like Cyril in The Decay of Lying) he can rationalize his lying:

Truth can never be spoken (Nothing is ever quite true’, 91), only hinted at in paradoxes. Lord Henry is ‘Prince Paradox’ (215). He sounds like Lao Tzu:

To use another circus metaphor, he is a juggler with words. The book is full of wordplay and playing with words. For instance, even when Dorian Gray is talking seriously, a pun is put into his mouth (‘It sounds vain… Sybil Vane’, 232). For Wilde, words are a game. This idea is actually made explicit:

The game-metaphor (juggling again) has been used before in the book:

In the playful interchange (pages 215-219), itself an elaborate verbal game, ‘riposte’ (219) a term from fencing is used. Another sporting metaphor applied to speech occurs earlier:

Lord Henry plays cat to Dorian’s mouse:

There is something of the seductive siren in Lord Henry:

Something similar is said of Sibyl Vane (and her name is obviously significant in this context):

There is a suggestion of the Pied Piper (cf ‘they followed his pipe laughing’, 50) Words affect action. They may lead astray, deprave and corrupt. Dorian is warned:

If a person is influenced, he becomes ‘an actor of a part that has not been written for him’ (25). This is what happens to Dorian. He even begins to speak like Lord Henry. Basil notices the change in his speech quite early: ‘It was so unlike Dorian to speak like that’ (34). In the face of Lord Henry’s overwhelming rhetoric, Dorian can only falter:

The effect of words is made explicit:

Lord Henry’s words alter Dorian’s sensibility and stir him into action:

Dorian puts Lord Henry’s words into practice:

and this is his undoing. He says to Lord Henry: ‘You cut life to pieces with your epigrams’ (110). However, Dorian, not content to confine his cruelty to cutting words, acts out his sadistic metaphor and actually cuts life to pieces with a knife! Indulging in wishful thinking, Dorian says:

But his words come true, and the oath is exacted. It would seem to be just as well most words of that kind remain vox et practerea nihil. Words sometimes have great power. Dorian murders Sibyl with his unkind words:

A few words written on a piece of paper have power over Alan Campbell (189). Dorian murders Basil because of his words:

Lord Henry’s rhetoric wipes away Dorian’s doubts, he justifies his cruel actions with plausible words:

Unpleasant facts can be glossed over with specious words or simply ignored in conversation:

Therefore, words are subject to censorship:

In the world of Dorian Gray, only appearances matter. So, on the same day as making a body disappear, Dorian can indulge in society talk (194 ff). But sometimes, words may be seen to be inappropriate:

So, although words may influence action, words may also be ‘separated from action’ (149). The split is particularly pronounced in Lord Henry. Basil observes of him:

This may amount to hypocrisy:

Yet, paradoxically, it has been seen that putting words into action is not necessarily desirable either! The life of words and the life of action seldom coincide, the former often being the substitute for the latter:

It is even suggested that words (like poetry, Auden would have us believe) make nothing happen:

though it is elsewhere explicitly stated that words do alter things. There is more than a hint of paradox here. Lord Henry speaks with such style and verbal polish that he sounds unspontaneous. It’s as if he delivers carefully rehearsed lines like an actor. Indeed, he consciously performs for an ‘audience’ (50). The Vane family act like characters in a melodrama:

Dorian acts out a scene with his valet (178-9). But, after so much acting, Dorian is no longer taken seriously:

He is taken for an actor, when he is being sincere:

So much acting and lying makes communication difficult if not impossible. In fact, one could say that failure of communication is the rule rather than the exception. Characters do not listen to each other:

or they cannot understand each other:

Or they cannot find adequate words:

Communication is denied:

Dorian tells Basil: ‘Don’t speak!’ (126) and a little later Basil tells Dorian the same: ‘Don’t speak!’ (128) Words are devalued by being given perverse definitions:

Lord Henry sounds like Ambrose Bierce in The Devil’s Dictionary:

Such an assault on language may render it meaningless:

Dorian is so corrupted that not only his diction but also his understanding of language is affected. When Basil quotes the Bible, Dorian replies:

On one level, language is noise. Sometimes that’s all it is, a meaningless noise (‘drunkards bawled and screamed’, 204), a noise to drown other noises:

Human language is juxtaposed with animal noises:

Sometimes, the two become indistinguishable.

Lady Brandon has a voice like a peacock’s (13), Sibyl Vane that of ‘nightingales’ (60). Animal noises are more spontaneous, perhaps even more communicative than words. Intense emotion expresses itself directly and forcefully without words:

The subsequent verbalization is to no avail. Dorian acknowledges Sibyl Vane’s death with his cry but denies it with his empty words: ‘Sibyl dead! It’s not true! It’s a horrible lie’ (111) It is significant that Dorian dies with a wordless cry (‘horrible in its agony’, 247) – communication more primal, immediate and sincere than any words. After the inadequacy of trivial chatter and the irresolvability of paradox, Dorian despairs of language and resorts to inarticulate sound:

When word fail, there is silence. The word ‘silence’ and its variants occur again and again (eg 33, 46, 55, 71, 101, 112, 117, 189, 196). Silence, though sometimes pregnant and eloquent, usually suggests a lack or failure of communication. It seems something to be avoided:

But amid so much small talk and society gossip, Mr. Erskine’s ‘bad habits of silence’ seem almost wise:

At least, he avoids empty words. The others go on talking, with nothing to say. Words are inadequate to convey deep emotion: Basil who repeatedly warns Dorian about his corrupting words, work at his art in silence:

Dorian was born of silence (his mother stopped speaking to his father, 42; ‘Months of voiceless agony, and then a child born in pain’, 44) and words are to blame for his downfall. In the end, after Dorian’s last word has been said, silence is regained: ‘Everything was still’ (248) * Davy King, 1974The Picture of Dorian Gray was first published in 1890 (All page numbers refer to the Penguin Modern Classics edition of The Picture of Dorian Gray) |

|